Twenty percent of customers defect because of a poorly executed transition or integration.[i]

“Customer defections are a major reason why more than half of all mergers fail to deliver the intended improvement in shareholder value….”[ii]

Startling statistics, aren’t they?

As longtime business owners know, markets don’t write checks, customers do. Those customers are the result of strong relationships built on their experiences with you and your company year after year, and on your company’s perceived value and trustworthiness.

When you sell your business, that relationship is tested.

With all due respect, we put our time and focus on shaping up our business for sale, vetting buyers, dealing with investment bankers and lawyers, but leave the customer adrift and open to competitor enticements. As a consequence, sustainable revenue (and our business valuation) is at risk.

Anticipate Customer Reaction

Whether a customer has a positive, wait-and-see, or negative reaction when they hear you are transferring ownership depends on two things: their history with you and what they know or are guessing, assuming, and sometimes fearing about the change.

Yet defections don’t have to happen if you pay attention to the four major factors that cause them.[iii]

- How close and trusted the relationship is with you, based on years of shared experiences—as well as how closely linked your relationship is, such as prime/sub-prime contractor relationships.

- The relationship of the customer to your prospective buyer(s), e.g., previous negative experiences as a customer or a competitor of the new owner; or concern they may have about how the relationship will change, e.g., with a sole source agreement.

- The amount of mutual and accurate information about buyer and seller intentions for the sale and how changes might impact them, such as cycle time or customer costs.

- How much turbulence there is (or might be) in post-close operations that negatively impact customer operations or cash flow, such as changes in logistics, billing/payment, or contracting processes.

Two Prevention Strategies

To prevent defections, you must be able to proactively address these four factors. Capitalize on where you are strong, and mitigate any weaknesses in those four areas. Here are two prevention strategies.

Conduct a Customer Relationship Audit

Just as what’s known and unknown about the change creates instability for your customer, what you know and don’t know about your customer is the key to preventing instability.

Spend time gathering the following data:

- What do you know factually about the most important customers in your portfolio—those who drive 80 percent of your revenues? For example, do you know their size of your revenue pie, contract expiration dates, or your vulnerability to competitors taking your place?

- What do you know personally about those customers as a fellow business owner, such as “what keeps them awake at night”—what their values and goals are and what support they will need to make the transition to your buyer?

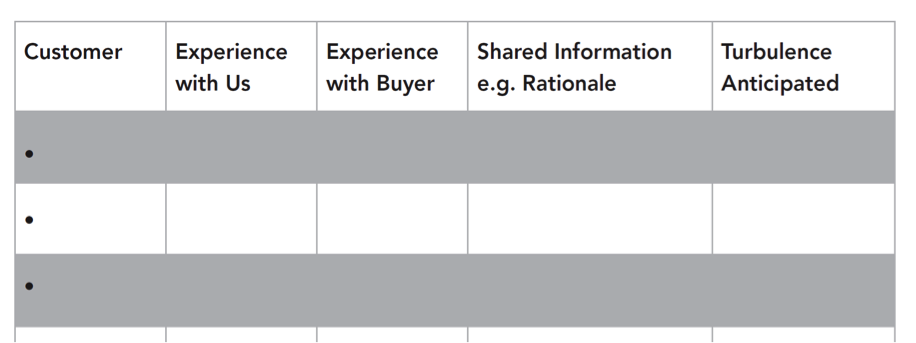

Characterize these relationships and determine the amount of shared information.

- How would you characterize your top customers’ experiences with you/your company? What is their experience with your potential buyer?

- What is the information these top customers have about your goals, the sale, and a potential buyer, and what is their understanding of it (e.g., assumptions they are making)?

- What turbulence might they experience from a change in owner?

Build a Customer Transition and Communications Plan before the close.

- Develop an action plan. With this information you can define the implications for retaining customers before and after the close. What information do your customers need to feel secure in maintaining their relationship with you? What plan can you share to assure the least turbulence and deliver a smooth transition in logistics, administration, and policy? Customers need confidence in a plan and your goodwill.

- Expect a large debate among brokers and advisors about communication with customers prior to the close of your sale, especially in commodity-type businesses, professional services, and medical practices.

Yes, customers are change-averse. Yes, they buy “you” and not just the service/product. They may hate the deal. Some say to tell customers as late as possible, so competitors can’t use customer anxiety over the sale against you.

That argument only has merit if:

- Your customer relationship doesn’t allow open, candid conversation, and doesn’t allow you to surface and work through concerns or resistance.

Information about your business being for sale (or your retirement) isn’t going to become known anyway, i.e., before you make it official, which could leave you reacting to comments like, “How come I had to hear this from…?”

Information about your business being for sale (or your retirement) isn’t going to become known anyway, i.e., before you make it official, which could leave you reacting to comments like, “How come I had to hear this from…?”- You don’t have a transition and communications plan (although you should have one! Research shows transition and communications are critical to mitigating negative reactions).

My bias is to plan communications using your customer knowledge and relationship, providing information that corrects misassumptions, reduces anxiety, and builds confidence in the post-close transition. This requires a face-to-face, President-to-President series of interactions. This is a high-touch moment in your leadership.

Peter Drucker wrote, “The purpose of business is to create and keep a customer.” Both you and your customers want the least disruption in revenue and relationships. In the best cases, the transition actually can build enduring loyalty between you and your customers, because during this transition time you demonstrate your respect; you listen and share information; and you work toward a common goal of sustainability.

Photo courtesy of Véronique Debord-Lazaro.

[i] Laura Miles and Ted Rouse, “Keeping Customer First in Merger Integration,” Bain & Co. 2011.

[ii] Laura Miles and Ted Rouse, “After the Merger, How Not to Lose Customers,” The Wall Street Journal, March 14, 2012.

[iii] For an in-depth look at customer reactions and implications see Christina Oberg, “The Importance of Customers in Mergers and Acquisitions,” 2008, Department of Management and Engineering, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden.